INTRO & DISCLAIMER:

This is a written resource intended to be supplemental to my workshops on The Stability Spectrum. Most of what is written below will be useful as a stand alone source of information. If something needs clarification, it is likely because this is support for a real-time course, not included. Chances are, an online search will help you to gain further understanding. Or, if you have specific questions or concerns please drop them below in the comments. Remember, I’m a yogi and do not hold a doctoral degree in any medical or sport-related field. Use this information appropriately and with guidance from your doctor if there is any question at all about its safety or efficacy for you, personally.

WHY AM I TEACHING THIS WORKSHOP SERIES?

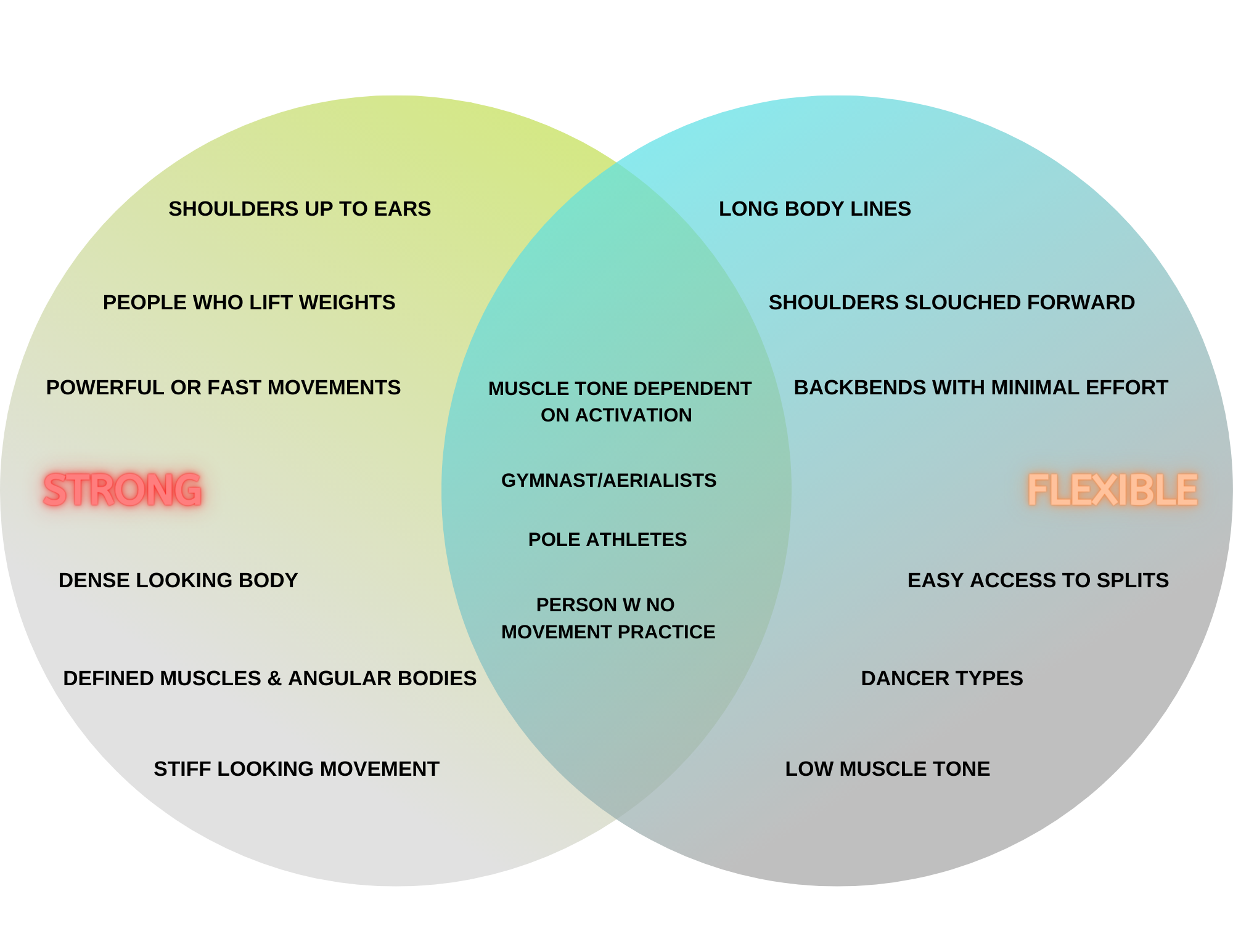

I’ve been teaching yoga since 2014. I’ve been coaching other movement since 2012 and I’ve been an athlete my whole life. I’m a trained researcher and have spent years accumulating knowledge outside of the academic context to apply to my own body or to give me a different lens by which to view the bodies that come to me for training. In the process of teaching and observing others, I noticed people tend to cluster toward one or the other starting place in their movement endeavors. They are either in Group A - “Flexible” or they are in Group B - “Strong.” I’ve made a diagram to illustrate my thinking. These are loaded terms but I’ve chosen them for a reason - because they both highlight what are considered to be desirable traits AND you don’t need to know special terms to get the idea I’m trying to convey. They do not, however, do a good job of describing what’s going on beneath the surface for either group. We will get into that momentarily. For further illustration of the point, see the graphics below. CAVEAT: we are working off of stereotypes so don’t get too invested…

Static and Motion based characteristics of “strong” and “flexible” people with some examples of overlap.

On the left sample “strong” bodies from a basic Instagram search #strong and on the right an Instagram search for #flexible

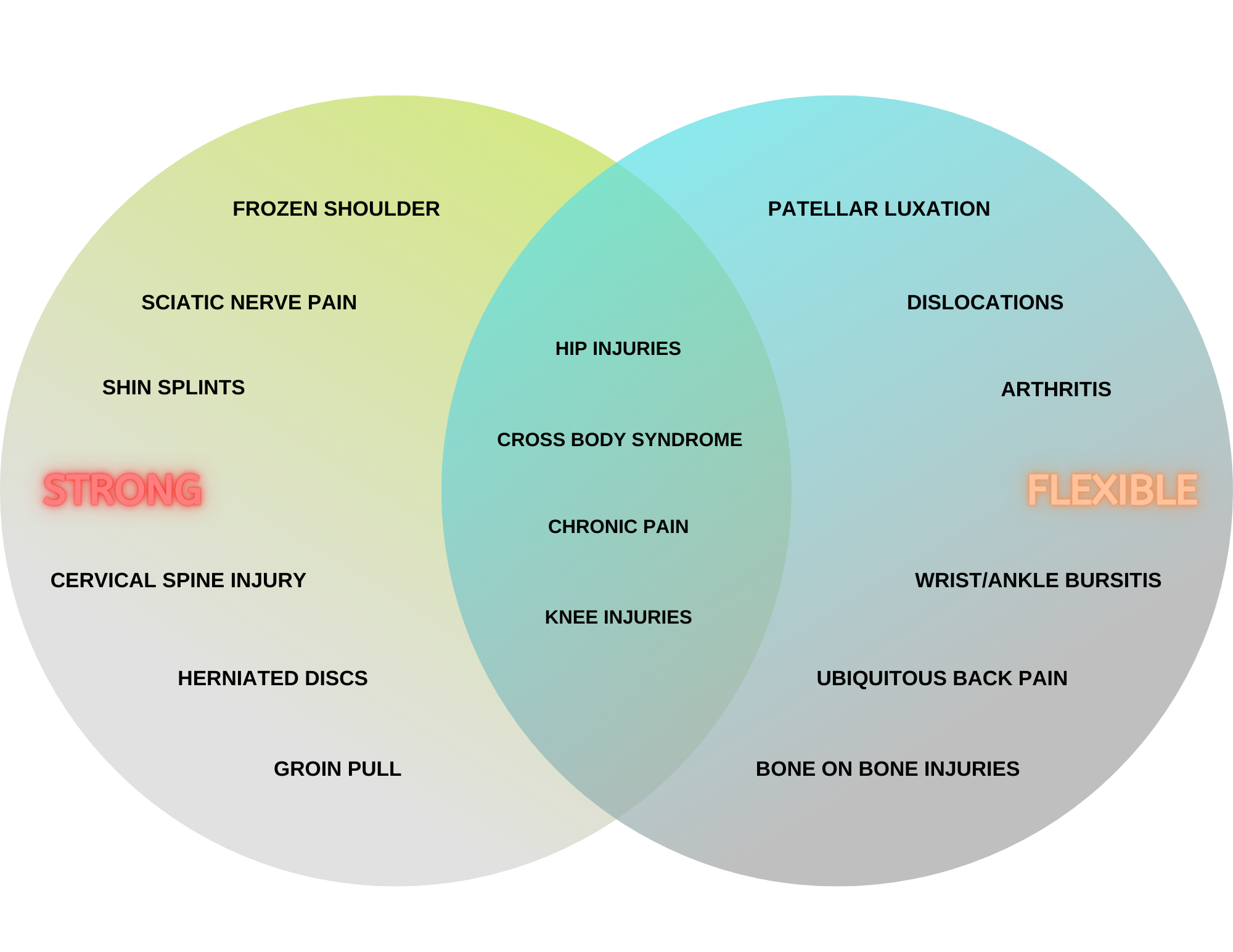

Injury happens, discomfort happens, pulled muscles happen, compressed vertebrae happen…right? Yes. They do. But they don’t have to, at least in theory. The two groups above, in addition to having distinct characteristics of what they look like standing and in motion, also have a tendency to accrue injuries, aches and pains and maladaptive motor patterns in divergent ways; with some areas of overlap as well.

Classical injuries/ailments experienced by “strong” or “tight” people, classical injuries/ailments experienced by “flexible” or “hypermobile” people and areas of overlap.

WHY CONTINUED…

In my personal experience I started in the “strong” category. I have experienced stiffness, discomfort, an inability to find good alignment in hand balance leading to chronic shoulder pain, sciatic nerve pain from a hamstring pull, etc. Over the years I have healed all of the above and am continuing to evolve my practice.

It so happens that, of my private clientele, more than half are working with me because of injuries related to hypermobility. These include patellar luxation, bunions, bursitis, hip capsule injuries, etc. We are continually working to re-train motor patterns that keep my clients’ bodies safe.

But in my everyday teaching experience, of which I have accumulated about 4,000 hours, I see people like me and people like my private clients mixed together in a class. As I gained experience, I started to notice these different populations. Listening to students, I started seeing patterns and how a standard yoga class assumes a body that possesses both strength and flexibility as a starting point, when in fact, many people are lacking in one or the other and sometimes both in drastic ways.

This online resource and the accompanying workshop are my first attempt to codify some of what I have observed over the years both in terms of problem areas and in terms of tools to resolve the problem areas. The good news is, the methodology is more or less the same for both groups of people! So below we will get into more technical definitions of “strong” and “flexible,” how to identify those patterns in yourself and from there we will take a look at some resources I’ve found to be of great efficacy over the years.

Definitions

As previously mentioned, the terms “strong” and “flexible” are good to get started but otherwise inadequate for the following conversations. So, let’s keep the general concepts but replace those two words for more meaningful terms.

In this conversation we will now convert “strong” to “stable.”

Stability is the ability to maintain or control joint movement or position. Stability is achieved by the coordinating actions of surrounding tissues and the neuromuscular system.

Instead of “flexible” we will now use “mobile.”

Mobility is the degree to which an articulation (where two bones meet) can move before being restricted by surrounding tissues (ligaments/tendons/muscles etc.) - otherwise known as the range of uninhibited movement around a joint.

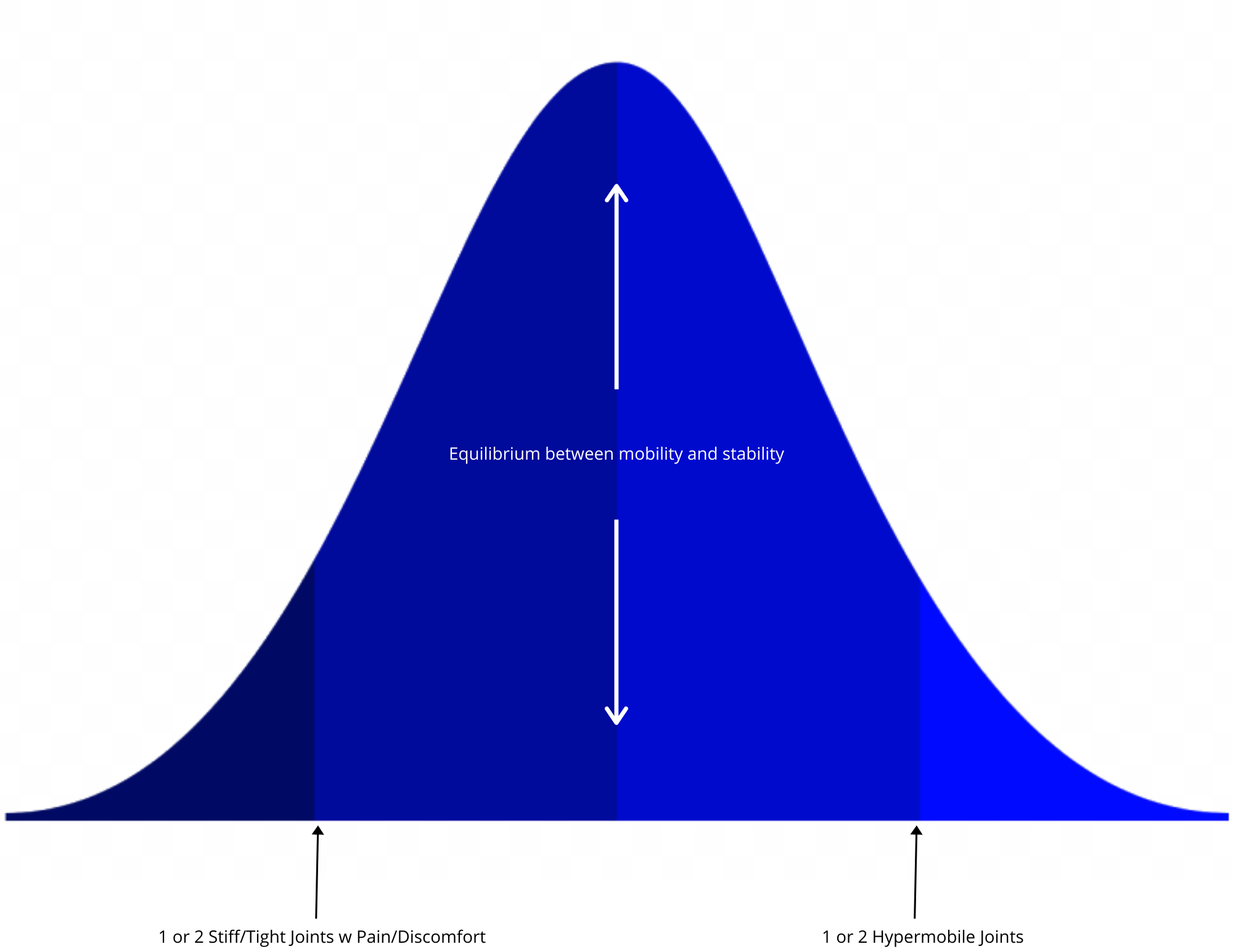

In an ideal world these two abilities work together in tandem for a perfectly balanced system where no one get hurt except through external forces. But the real world looks like these two abilities being out of balance in most bodies to the degree that a person ends up in one or the other camp. To visualize this let’s bring back one of my favorite teaching tools from Psych 101 - the bell curve!

The Bell Curve

NOTE: The graphical depictions below are my approximation of things, not based on personal research or study. Real studies do exist if you want more precision.

The Bell Curve

The term "bell curve" is used to describe a graphical depiction of a normal probability distribution, whose underlying standard deviations from the mean create the curved bell shape.

Let’s apply the concepts of the Stability Spectrum to the Bell Curve and see what we get….

0, .5 and -.5 on the Bell Curve with our variables applied. Notice how the Bell Curve is a spectrum with a big bump in the middle.

Referencing the version of the Bell Curve (above), we start at the zero-point or the middle. Here, a person has full use of their joints in a way that is supported by their muscles and other tissue. The given range of motion (ROM) for a joint is determined by examining a wide variety of factors including the shape of the joint itself. We will take a look at the other factors involved a little later as most of the variables factor into where a person falls on the Stability Spectrum. You will also notice above, two points equidistant from the center. If we were talking pure numbers these points would be labeled .5. That is to say they are about half of a point away from the mean, taken here to mean the statistical average. On the Bell Curve, whatever is being measured is less “average” the further away from the middle it gets. At .5 away from the middle, you’re still looking at things most people would consider normative. In our example, someone who has one or two stiff joints or someone who maybe has open shoulders even though their hips are tight would not be considered extreme cases (we will discuss exceptions in the workshop). Since in reality most people don’t have full range of motion with support from surrounding tissue, the above is an idealization. In most circumstances, if you were to actually measure people and create a statistical average ROM, the mean would probably skew toward the tight side of things. The Yoga Dojo is an example of a community or cohort where, perhaps, the mean would skew toward the mobile side.

The Bell Curve - Tails

The further you move away from center on the Bell Curve the further you get from the statistical average. Here is 1+, using our model of mobility. At this point, the manifestations begin to look extreme compared to the middle of the pack.

Here’s where the conversation gets a little interesting. The further you move away from center the higher the number. So this Bell Curve (above) shows +1 and -1 and beyond. This is where, the people in our discussion would start to have congenital joint issues like club foot, or on the other end have Ehler’s Danlos Syndrome. The size of the Bell Curve drops off steeply here. That is because there is a rapidly diminishing number of people at each point. The two differently colored ends of our spectrum or Bell Curve are called the “tails.”

It is through examining the "why” behind the conditions at the tails that we get a really good understanding of what is at play for the rest of us back toward the middle.

Factors

Where you fall on the Stability Spectrum is going to be a combination of many factors. Your joint ROM is the quickest and dirtiest assessment of where you fall. As mentioned previously, there are multiple factors influencing ROM…

Bone Morphology - The shape and angles of the bones in the joint and leading into the joint. For this purpose you can think of all joints as simple machines. The length of the limb leading into the joint will create different leverage and torque in addition to the shape and angle of the joint itself. Ex: Press Handstands

Movement Practices - the regular degree through which a joint is asked to move. Ex: Sedentary lifestyle vs. Professional Athlete

Tissue Properties - Muscles, ligaments, tendons, even skin surrounding a joint have a predisposition to different properties. The assumption is that these tissues are all functioning normally. Changes in tissue function effect the stability or mobility of a joint.

Genetics/Diet/Age - The genes you inherit influence your morphology, tissue composition, how your body processes the raw material you consume as food and how these variables evolve over the course of your lifetime.

Injury - Accute and chronic use injuries can impact one or more joint’s ROM in a sudden and drastic way.

When you’re measuring a “normal” body it is sometimes difficult to see how the above factors relate to one another. It can be hard, for example, to look at my own body and say “Well what came first? Tight muscles? Tight ligaments? Is the tightness genetic? Is it emotional?” We have the people living in the tails to thank for some of the greatest insights about our body as a system. It is through studying communities like the EDS community, that we are able to understand the role genes play on collagen formation and thus joint health. It is through observation of patients undergoing physical therapy after surgery and injury that we are able to examine how large changes in ROM effect the body as a whole. The body is indeed a system. It is very difficult and maybe impossible to isolate any ONE of the above factors as being the definitive reason for where you fall on the Stability Spectrum.

Assessment Tools

Baseline measurements can be found below as well as some definitions of extension, flexion etc:

A quick test for Hypermobility can be found below. Notice, we have not defined Hypermobility in writing. There is a wide range of what Hypermobility can mean and secondly there is no direct antonym or opposite. You can take it to mean greater than baseline ROM in one or more joints OR you can find a more detailed explanation here. The quick test for Hypermobility is called the Beighton Score. There are two links below both showing the criteria for the test with some novel and redundant information:

So what about the tighter people reading this and participating in the workshop? For you we have some standard flexibility tests ala gym class in primary school. If you want to get fancy - grab a friend, a protractor, ruler and tape measure. The tests after the link below more or less run you through the ROM for your major joints. Get your friend to measure the angle with the ruler and protractor and some of the sit and reach scores with your tape measure. That is what we will be doing in the workshop!

Final Thoughts for Pt 1

Ok, how’d you do? If you came away with a couple of hyper mobile joints, congratulations! You are in the approximately 25% of the population who has one or two hypermobile joints. If you your self assessments or the definitions on the Hypermobility page started sounding alarms, this would be a good indication to follow up with your doctor. Severe connective tissue disorders are rare BUT maybe some of the aches and pains you experience are related. Part 2 of this series will address some immediate tools you can use and modifications you can make to your movement to keep you safe in the mean time.

Tight? Chances are you already knew it! But likewise, if you are experiencing limitations in a generalized way, or severely in more than one joint, that’s what part 2 is for.

Perfectly balanced specimen? More power to you my friend. Chances are you already do some of the exercises and drills I’m going to show everyone in part 2. Join us anyways and be my movement model!

Knowledge is the key to moving forward. We aren’t conducting peer reviewed double blind experiments here, but if you can’t use yourself as your life’s greatest experiment and keep notes accordingly what are you even doing? These are the sorts of activities people used to do when screens didn’t exist. Its through just this sort of curiosity and experiment that yoga was born.

We are at a temporal nexus of ancient and modern knowledge coalescing. Disparate practices with esoteric focal points are pooling resources to evolve new Gold Standards. Its an amazing time to be a mover. Today, we know more about moving and the human body than every before. I’m looking forward to part 2 where I will share some of the best tools around for creating happy joints and healthy tissue that I’ve found in the past ten years.

Questions and comments below 👇.

Thanks! 😊🙏